The time is right to consider the transformation of RFBs to effectively address the emerging global challenges facing our member-countries and the rest of the world at large.

At the core of their hearts, Regional Fishery Bodies (RFBs) are an instrument for the conservation of the shared (transboundary, straddling and highly migratory) fish stocks. The RFBs balance their roles – within the organization they strive to prevent a race to fish among their members, while on the other hand, ensure that the regional effort matches the rest of the world’s expectations on the conservation of shared stocks. This external environment usually shapes up public and scholastic opinion about the performance of an RFB. However, in managing the internal environment, the slow process of changing the zero-sum games to positive-sum games is usually much less talked about

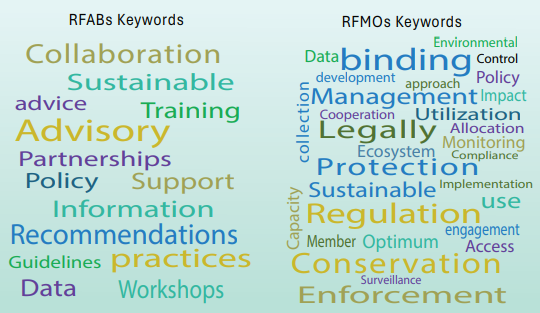

There are two main types of RFBs: Regional Fisheries Advisory Bodies (RFABs) and Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs). As the name suggests, RFMOs can make binding decisions for their member-countries, while RFABs usually engage in diverse, non-binding advisory activities to prepare their member-countries’ conservation activities, as depicted in the following word cloud of keywords from their mandates.

These differences in role and relationships (a country may be more comfortable discussing its issues in an RFAB setting, than in an RFMO setting; on the other hand, a country may see more benefits from RFMO which drive close-ended decisions rather than open-ended advisories as in the cases of the RFABs) can serve as a natural lab for discerning the best course of action for propagating regional cooperation in the future.

As we are rapidly getting close to the planetary boundaries while global inequality has remained threateningly sticky, human society will face a tough choice between competition and cooperation in the coming years. Differently stated, the option will be between aiming for short-term and long-term gain. However, more often than not, making such a choice is difficult, if not impossible. To start with, we have to decide how many years would qualify as long term and how many years as short term, though the choice will differ depending upon the situation and options. Can national aspirations be withheld for greater good? Many such difficult questions have to be answered as we weigh our options.

It is high time that we explore the implications of the relationship between RFBs and their members and whether RFBs should continue to remain a measure only for conservation. It is quite evident that relying solely on their traditional roles is insufficient in the face of the rapidly evolving and multifaceted challenges confronting global fisheries. The escalating impacts of overfishing, climate change, pollution, and habitat destruction demand a more proactive and dynamic approach to fisheries management.

“‘Pivoting’, a term popular in the corporate world, refers to the fundamental change in an organization’s strategy, business model, or operations to adapt to new conditions, technologies, or challenges. For RFBs, pivoting implies rethinking and restructuring their roles, methods, and operations to address contemporary challenges in fisheries management more effectively ”

At BOBP-IGO, we are constantly asking the question as to how we can generate more value for our member-countries. For example, over the years, BOBP-IGO has played an important role in capacity building, focussing on bridging the current gaps in performance. While that is necessary, we are increasingly working with the countries to achieve the future we want.

We visualize transformation of our capacity-building activities gradually to ‘capability nurturing’ and ‘incubation activities’, where countries frame the bigger picture and strive towards it. A baby step towards this direction was to create thematic knowledge networks and nurture them to develop focussed knowledge products. Establishment of BOBSAN, the regional network for stock assessment practitioners, provided an opportunity to appreciate the variations in practices and opportunities for cross-learning. The network has identified for itself a set of focussed tasks through virtual interaction and collaboration with the support of BOBP-IGO. In addition, BOBPIGO has created a funding platform to operationalize the research network among the marine science researchers in the region through its BIMReN initiative – BIMSTEC-India Marine Research Network. The IGO is actively engaging at different levels of the fisheries production system with the full agreement of the national member governments to locate potential areas and nurture them. BOBP-IGO is leveraging these platforms and the regional projects to keep the conversation going in track 1.5 and track 2 avenues of dialogue.

Sculpting a regional goal while being fully considerate of national goals will be increasingly important in the days to come. The BOBP-IGO is already working towards it, but there is no roadmap or example to follow. It’s a journey of trials and errors; and of small and big triumphs.

To sum up, the future of RFBs depends on how well they become integrated into national strategies. This will, of course, depend on how successful we are in communicating the need for cooperation and the shared nature of our systems.

The RFBs of the future need not be platforms only for negotiation and haggling but also for knitting a common future and talking freely about national needs and asking support without the sense of being judged, lacking, or lagging.

“The time is right to consider the transformation of RFBs to effectively address the emerging global challenges facing our member-countries and the rest of the world at large. The evidence underscores the fact that the traditional roles of RFBs—centred around data collection, limit setting, and enforcement—are no longer sufficient in the face of complex and interconnected global challenges. ”

RFBs possess a wealth of historical experience, established relationships, and operational frameworks that can be optimized to meet contemporary demands. Integrating advanced technologies, developing adaptive management plans, and including a broader range of stakeholders are necessary for RFBs in this changing scenario. Addressing the socioeconomic dimensions of fisheries management and the need for equitable participation of developing countries should be prioritized. Providing technical assistance, capacity building, and financial mechanisms ensures all member countries benefit from sustainable practices.

“The transformation of RFBs into agile, adaptive, and inclusive organizations is not just an option but a necessity. This evolution is essential for maintaining the sustainability of marine resources, protecting biodiversity, and ensuring the livelihoods of millions who rely on healthy ocean ecosystems. ”

The argument is compelling: by reimagining and strengthening RFBs, we can build a resilient and effective framework for global fisheries management that meets the demands of the 21st century.